Peacock Mantis Shrimp

Found in the Indian and tropical western Pacific oceans, the peacock mantis shrimp is a candy-colored crustacean known for its ability to quickly “punch” prey with its front two appendages. According to Oceana, the international ocean preservation advocacy group, this shrimp’s punch is one of the fastest movements in the animal kingdom—so much so, that it’s strong enough to break an aquarium’s glass wall. But no worries: They mostly only use their fists of steel to break open mollusks and dismember crabs.

Pink See-Through Fantasia

Its name makes it sound like a piece of sexy lingerie, but don’t be fooled: the pink see-through fantasia is a sea cucumber, found about 1.5 miles deep into the Celebes Sea in the western Pacific, east of Borneo. It was only discovered a little over a decade ago, back in 2007, but the curious sea cucumber has a survival tactic that points to its longtime evolution: bioluminescence to ward off predators. The pink see-through fantasia is named for its transparent skin, through which its mouth, anus, and intestines are all visible.

Frogfish

It’s so easy to miss the frogfish, because these types of anglerfish (there are over 50 species of them) are nearly identical to their surroundings—mostly coral reefs. They resemble sponges or algae-covered rocks and come in pretty much every color and texture imaginable. Some frogfish even use their camouflage not to hide, but rather, to mimic poison sea slugs. No matter their appearance, one thing all species of frogfish have in common is their strange mode of locomotion. Although they can swim, most walk along their pectoral fins, which have evolved into arm-like limbs, including a joint that resembles an elbow.

Ribbon Eel

Usually seen nestled into burrows around coral reefs, the ribbon eel (sometimes called the leaf-nosed moray eel) lives in Indonesian waters from East Africa, to southern Japan, Australia, and French Polynesia. The juveniles start out black, with a pale yellow strip along the fins, and as they grow, transitions to a bright blue and yellow coloring. These eels are considered “protrandic hermaphrodites,” meaning they change sex from male to female several times throughout their lives.

Frilled Shark

The frilled shark, Chlamydoselachus anguineus, is one of the gnarliest looking creatures in the sea. If it looks like an ancient beast, that’s because it is: the prehistoric creature’s roots go back 80 million years. The frilled shark can grow to about seven feet long and is named for the frilly appearance of its gills. Although shark in name, these animals swim in a distinctly serpentine fashion, much like an eel. They mostly feed on squid, usually swallowing their prey whole.

Christmas Tree Worm

Scientists found this strange creature at the Great Barrier Reef’s Lizard Island and named it, aptly, the Christmas tree worm. The spiral “branches” are actually the worm’s breathing and feeding apparatuses, while the worm itself lives in a tube. These tree-like crowns are covered in hair-like appendages called radioles. These are used for breathing and catching prey, but they can be withdrawn if the Christmas tree worm feels threatened.

Box Crab

Like so many other sea creatures, the box crab is a master of disguise. In this case, the crustacean—which mostly keeps to the seabed—buries itself beneath the sand, with just its eyes protruding from the mucky depths. One of the most fascinating aspects of the box crab’s life cycle is its mating habits, which literally redefine what it means to be swept off your feet. When the male box crab has found its mate, it grasps onto her with its claws and carries her around the sea floor until she molts her shell.

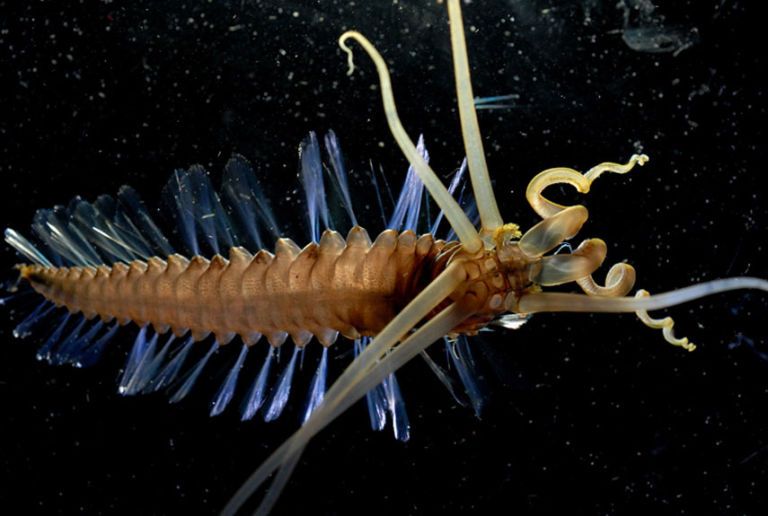

The Squidworm

Researchers with the Census of Marine Zooplankton first discovered the squidworm in 2007 during a cruise in a remotely operated vehicle some 1.8 miles underwater. The funky-looking fish is named for the 10 appendages protruding from its head, which look like tentacles. The squidworm uses these to collect debris falling from the open waters above, known as “marine snow.”

Giant Isopod

These guys are native to chilly, deep waters and can grow to be quite large; in 2010, a remotely operated underwater vehicle discovered a giant isopod measuring 2.5 feet. These crustaceans, which sort of resemble a massive woodworm, are carnivores and usually feed on dead animals that fall down from the ocean’s surface. Despite their discovery back in 1879, these creatures mostly remain a mystery. However, it’s believed that giant isopods grow so large in order to withstand the pressure at the bottom of the sea.

Nudibranch

With over 3,000 different species on record, the nudibranch is an extremely versatile kind of sea slug. These little guys are found pretty much everywhere, in both shallow and deep waters, from the North and South poles and into the tropics. There are two distinct kinds: dorid nudibranchs, which are smooth with feather-like gills on their back to help them breathe; and aeolid nudibranchs, which breath through a different kind of organ, also located on their backs, called cerata. Because the tiny nudibranch lacks a shell, it instead protects itself with bright camouflage, meant as a warning signal. But perhaps their wildest adaptation of all is the ability to quite literally swallow, digest, and reuse stinging cells from prey.

Sea Angel

Although they’re called sea angels, these creatures are actually predatory sea snails. This particular specimen, Platybrachium antarcticum, “flies through the deep Antarctic waters hunting the shelled pteropods (another type of snail) on which it feeds,” according to the Marine Census of Life. Sea angels have special parapodia, or lateral extensions of the foot, that help to propel them through the water.

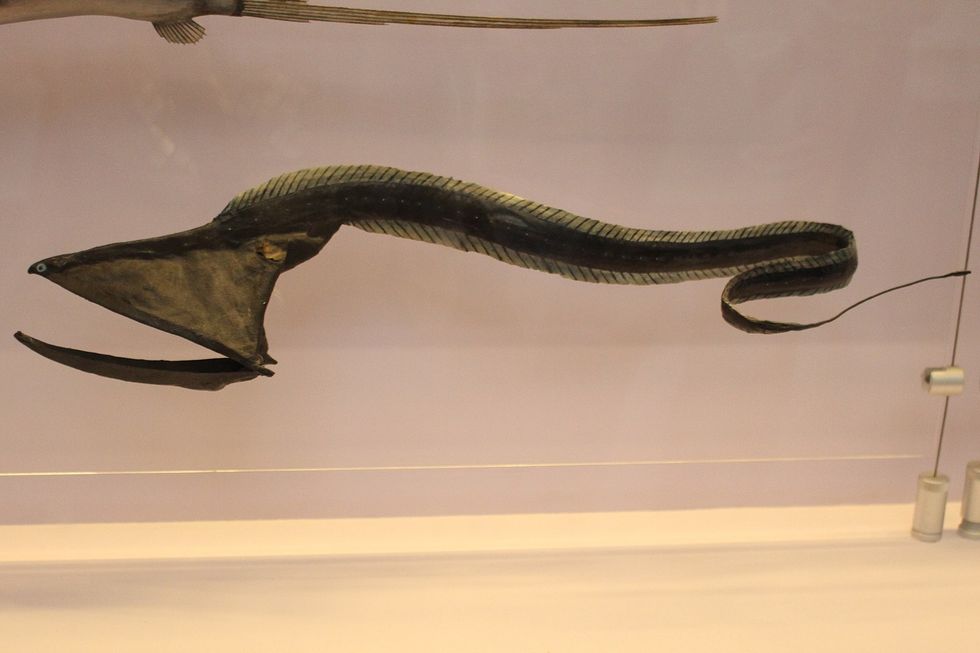

Gulper Eel

The gulper eel (also referred to as the pelican eel) is named for its massive mouth and jaw, which helps them to swallow prey whole. They can grow up to six feet in length and their huge mouths allow them to hunt down meals that are larger than them. This usually happens when food is scarce—it’s believed that gulper eels usually eat crustaceans and other small marine animals.

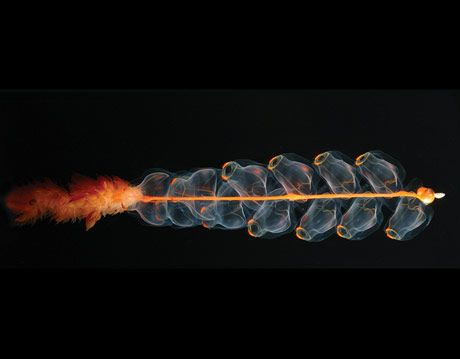

Marrus Orthocanna

Like a multi-stage rocket, this bizarre microscopic creature, Marrus orthocanna is made up of multiple repeated units, including tentacles and multiple stomachs. Technically, they are physonect siphonophores, which are related to the Portugese man o’war. Like ants, a colony made up of many individuals has attributes resembling a single organism.

Giant Squid

The Giant Squid, Architeuthis dux, is absolutely the stuff of nightmares. The largest one ever recorded came in at a whopping 43 feet long—nearly half the size of a blue whale. Earlier this year, scientists created a draft genome sequence for the giant squid, in a bid to better understand it. With about 2.7 billion DNA base pairs, its genome is about 90 percent the size of the human genome. Beyond that, scientists don’t know a whole lot about the giant beast or its habits, because most of what we know comes from their carcasses, which wash up on the shore. Most of the time, the giant squid lives in waters so deep that we never see them, adding to their intrigue.